I’m old enough to remember when smoked salmon had a touch more glamour than it might do now but chat around smoked salmon socialism made me wonder again where phrase had come from.

From using it in the company of English people I had become aware that smoked salmon socialism is a term unique to Ireland, although there are many variations of the insult. The English version is the ‘champagne socialist’ defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as ‘a person who espouses socialist ideals but enjoys a wealthy and luxurious lifestyle’, and then there is also the more extreme version of Bollinger Bolshevism. Since the late 1980s, ‘Chardonnay liberal’ has been used in Australia to describe ‘guilt-ridden rich an bleeding hearts’ according to S. Margot Finn, author of Discriminating Taste: How Class Anxiety Created the American Food Revolution, who noted how ‘criticism of the liberal elite across the Anglophone world often explicitly invokes high-status foods.’ The phenomenon is also used outside the English-speaking world, however, with Michael Symons writing in Meals Matter: Radical Economics Through Gastronomy adding gauche caviar (France) and ‘Toaskana-Fraktion (Germany) to the list of gourmet-related phrases used by right-wing commentators as slights against the maturing, countercultural generation, perhaps somewhat similar to the type described in Tom Wolfe’s ‘Radical Chic’ essay. It is more an insult than an archetype such as the more recent breakfast roll man.

Champagne socialism seems to have been first coined by G.C. Eggleston in 1906 who used it to contrast with ‘beer socialism’, although I can’t speak to the beginnings of its use in Continental Europe. With the notable exception of rare individuals, most notably Countess Markievicz, there was no upper class, well-heeled left to be found in twentieth century Ireland. The left was predominantly the preserve of the working and lower-middle classes, and based on the trade union movement. Socialism of any variety was quite taboo in Ireland until the middle 1960s. Before then, the word ‘socialism’ was never used, with descriptions such as ‘progressive’ being preferred by those on the left. This was similar to the United States where socialism was tantamount to communism. However as socialism became fashionable among youngsters and a certain intellectual set, it went from something which was never used publicly to quite the buzzword.

Left wing middle class university lecturers, broadcasters such as Conor Cruise O’Brien, David Thornley and Justin Keating joined Labour to the point where the leader of the Irish Labour Party could promise ‘the seventies will be socialist’, an optimistic assertion that was not borne out but provided much mirth to cynics in the decades after. This set were often objects of derision in Fianna Fáil, particularly during the 1969 general election when, under the guidance of its director of elections, the Minister for Finance, Charles Haughey, it ran a red-scare against Labour which, it warned planned to nationalise farms and industries including Guinness.

Left wing middle class university lecturers, broadcasters such as Conor Cruise O’Brien, David Thornley and Justin Keating joined Labour to the point where the leader of the Irish Labour Party could promise ‘the seventies will be socialist’, an optimistic assertion that was not borne out but provided much mirth to cynics in the decades after. This set were often objects of derision in Fianna Fáil, particularly during the 1969 general election when, under the guidance of its director of elections, the Minister for Finance, Charles Haughey, it ran a red-scare against Labour which, it warned planned to nationalise farms and industries including Guinness.

Labour fared badly in the 1969 election but in at the next general election in 1973, it joined with Fine Gael in a coalition government with Fine Gael, with prominent members of the intellectual set serving as ministers. One weekend in early October 1974, Charles Haughey gave a prepared speech to a Fianna Fail function in Dublin in which he accused the Government of having lost its grip on the financial crisis, claiming that the ‘smoked salmon socialists’ had no real understanding of the basic needs of the economy. With its alliterative sibilance, it was a catchy turn of phrase. Arguably Haughey’s use of the description ‘socialist’ implied an insult in itself. At the time Irish smoked salmon was regarded as some of the best in the world and it was a luxury food, beyond the general means of most. When Haughey used it, it was to mean that these men were pointy-headed, out of touch men, with a suggestion that they were more socialite than socialist. Perhaps there was something of a nod to Harold Wilson’s beer and sandwiches at No. 10.

Though a former Minister for Finance, by this point Haughey was a backbench member of the opposition, where he sat in some disgrace after the Arms trial four years earlier. His description won attention for the speech that might not have been given to less florid, standard critique of macroeconomic policy. In the next day’s Irish Times, Donal Foley opened his Man Bites Dog column with a skit about ‘Mr. Charles J. Haughey, T.D. (‘Champagne Charlie’ to his friends)’ having ‘sent the names of a number of Smoked-Salmon Socialists to the Attorney General, Mr. Declan Costello, Bord Iascaigh Mhara, in conjunction with the Special Detective Unit.’

The phrase was sufficiently memorable that politicos assumed it was ghosted, although the following weekend, the Irish Times columnist John Healy, who was something of an associate (and sat beside Donal Foley in the newsroom), used his Backbencher column to admit “my friends accused me of giving [Haughey] the ‘smoked salmon socialists’ line. Not guilty, I fear.” Notwithstanding Healy’s denial, the phrase was sometimes credited to him including during a Dáil debate which featured an exchange over whether or not the salmon in question was smoked.

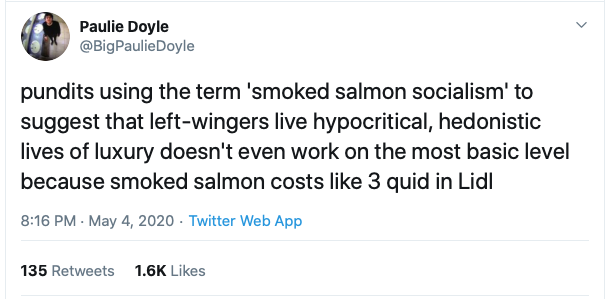

It was a description which stuck but while it evoked a particular milieux in 1974, it became distinctly anachronistic. Used against Labour members during a 2004 Seanad debate, Senator Brendan Ryan complained that smoked salmon was ‘a little dated. If the men in this Chamber did their own shopping, they would know that smoked salmon is far from the most expensive commodity. The real problem is that most of the men on the other side of this Chamber would not recognise smoked salmon in a supermarket because they remain traditional men, who believe shopping is women’s work. They do not know what is going on in the world.’

Ryan’s call fell on deaf ears however, so that nearly fifty years after the phrase was first coined, new generations remain bewildered why a standard sandwich at the Ikea self-service canteen is a byword for notions and political cant.

Smoked salmon sandwiches – possibly more fancy in Italian.

Left wing middle class university lecturers, broadcasters such as Conor Cruise O’Brien, David Thornley and Justin Keating joined Labour to the point where the leader of the Irish Labour Party could promise ‘the seventies will be socialist’, an optimistic assertion that was not borne out but provided much mirth to cynics in the decades after. This set were often objects of derision in Fianna Fáil, particularly during the 1969 general election when, under the guidance of its director of elections, the Minister for Finance, Charles Haughey, it ran a red-scare against Labour which, it warned planned to nationalise farms and industries including Guinness.

Left wing middle class university lecturers, broadcasters such as Conor Cruise O’Brien, David Thornley and Justin Keating joined Labour to the point where the leader of the Irish Labour Party could promise ‘the seventies will be socialist’, an optimistic assertion that was not borne out but provided much mirth to cynics in the decades after. This set were often objects of derision in Fianna Fáil, particularly during the 1969 general election when, under the guidance of its director of elections, the Minister for Finance, Charles Haughey, it ran a red-scare against Labour which, it warned planned to nationalise farms and industries including Guinness.