‘The Schoolmasters’ Rebellion: Teachers, the INTO and 1916

Published in Saothar 41 (2016)

On Saturday 13 May 1916, the day after the last of the executions which followed the Rising, J.P. Mahaffy, the Provost of Trinity College Dublin, sat down to write a letter to the Times of London. Mahaffy, who had entertained Prime Minister Herbert Asquith at his college residence that day, was furious at John Dillon’s speech to the House of Commons the previous Thursday. Dillon had told the Commons that hundreds of people had been arrested and ‘shot without any form of trial’ and, pointing to events in Paris in 1848 and 1870, Mahaffy took issue with his remark that ‘no rebellion in modern history [had] been put down with such blood and savagery.

But having lambasted Dillon and, naturally the ‘Sinn Féiners’ themselves, Mahaffy turned his attention to those he regarded as responsible for the rebellion in the first place. ‘There has been throughout the national schools a propaganda of hatred to England on the part of the schoolmasters living on the salary of the Imperial government,’ he asserted, ‘The rising generation have been so carefully soaked in disloyal sentiments that the large majority of the population is now against Imperial law and order.’ At this point, the provost was prepared to offer only one practical suggestion, that anyone in receipt of a salary from the Crown, particularly teachers but especially national teachers, would be required to make periodic public declarations of loyalty in the presence of the whole school that they were loyal subjects and would avoid all teaching of disloyalty or rebellion in their classrooms.

So began the notion of the Easter Rising as ‘the schoolmasters’ rebellion’. The idea that the national teachers of Ireland had been preaching sedition from the blackboard was repeated in the Times Educational Supplement in June which stated ‘there is evidence that in many National Schools the teaching of late years has been distinctly anti-British. Stress has been laid on the ancient wrongs of Ireland [and] little has been said about England’s constructive work in recent times,’ and Mahaffy took to the Times once again at the end of June to reiterate his claims. ‘It can be proved to any man who will listen to the evidence of those who lived through the whole insurrection in Dublin that it was deliberately planned by the careful instilling of revolutionary principles in the teaching of many of our primary schools.’ Quite how Mahaffy had arrived at this conclusion was unclear. Having spent Easter week in TCD, where he had led the defence of the college, he had not had the opportunity to quiz the insurgents as to their motives, or the extent to which they had learned them in school but an outspoken unionist, Mahaffy was also staunchly anti-nationalist in culture and politics, and had been a vociferous opponent of the Irish language and the teaching of Irish history. This may have coloured his thinking, perhaps informed by the prominence of Patrick Pearse in the rebellion, but the idea that the national schools were hot-beds of sedition came as news to most people, not least the teachers themselves and the Board of National Education.

Until Mahaffy’s volley against their profession, the Rising’s most immediate impact on the INTO was that it had disrupted its annual congress which was beginning in Cork on Easter Tuesday. Many of those travelling to Cork had been unable to make it, with at least one principal from Dungannon having to hide out in a restaurant on Amiens Street for the week, after various misadventures on Sackville Street on Monday. Congress proceeded anyway, but those who had made it were characterised has having ‘an anxious preoccupied look, and it could easily be seen their hearts as well as their thoughts were far away,’ with ‘any news from Dublin?’ the predominant question of the day. Explaining its failure to publish recent issues, the Irish School Weekly referred to the ‘calamitous events of the past three weeks in Dublin’ which had prevented them from going to press, and hoped ‘that never again will events such as those which have practically paralysed all kinds of Dublin since Easter Monday last mast the tranquillity of the metropolis or the country.’ That, in effect, was all there was to be said about the matter, or at least it would have been, had Mahaffy not intervened.

His first letter, having appeared in a London newspaper, did not garner much attention but the repetition of the claims in the Times Education Supplement made it difficult to ignore and prompted the INTO president, George Ramsay, to write to the Freeman’s Journal to take issue with its ‘scurrilous references’ to teachers. Noting its remarks that ‘the Commissioners knew what was happening but were powerless to interfere with the centres of disloyalty’ Ramsay noted that it had, in the next breath, inferred that teachers dared ‘not be disloyal because they are ‘watched by inspectors and managers and disloyalty always involved the risk of loss of pension’.

Naturally, these accusations (and the Board’s alleged complicity) were considered by the Board of National Education. At its first meeting after the Rising, on 23 May, it decided to request a list of the national teachers who had been ‘implicated in the recent insurrection’ and proposed to consider the ‘entire question of the connection with the ‘Sinn Féin’ movement of persons either in the direct or indirect employment of the Commissioners’, and at the next meeting two weeks later, Mr. Justice (John) Ross, a Presbyterian and member of the privy council, called attention to ‘the desirability of taking steps to dissociate the teaching in the national schools from disloyal and seditious tendencies.’ There were, at this stage, no signs of disloyal or seditious tendencies from which to dissociate but, after some consideration and discussion, the Commissioners decided nonetheless to bring the heads of the teacher training colleges and representatives of the school managers to a meeting to consider ‘measures to prevent the spread of seditious tendencies amongst the national teachers.’ The INTO was not invited.

The Board also made inquiries among the inspectorate as to whether they had any evidence of seditious teaching or acts by the teachers. To no one’s great surprise, the inspectors came back virtually empty handed. They found no cases of seditious teaching but there were a handful of cases where teachers or trainee teachers, had shown themselves sympathetic to the rebels, most notably, a speech given by the former INTO president, Catherine Mahon, at a meeting to set up a branch of the National Aid association.

They also received reports from Dublin Castle informing them of incidents where named teachers, and in other cases pupils and trainee teachers, had been seen wearing ‘Sinn Féin badges.’ In these cases, the Board would contact the school manager (or the principal, in the case of students in the De La Salle training college), who would report back and almost always, the inquiry would result in an apology from the teacher, and the matter would go no further, with an instruction from the board that they abstain from anything of a similar character in future. Naturally, in addition to whatever investigations were made by the inspectors, the Board of Education also called upon the source of the claims, Mahaffy himself, to state on what evidence he [had] made certain statements in the public press as to the seditious teaching in the national schools, but Mahaffy did not deign to respond. On 21 July 1916, the Board issued a statement to the press summing up the results of its inquiries, namely that

two or three instances of disloyal teaching [had] been brought under notice and these charges are being investigated, but no evidence has been adduced which would warrant the conclusion that seditious teaching in the national schools exists to any appreciable extent.

In a teaching body of 5,700 men, the Commissioners noted (overlooking the seditious potential of the women teachers), only ten had been imprisoned, which hardly supported a charge of general disloyalty.

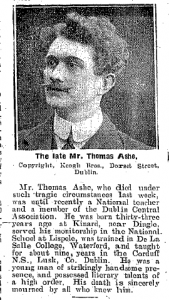

Overall, though, the Board was very cautious in taking action, even among the teachers who were directly involved. At it’s meeting of 26 September, it withdrew recognition from the two teachers who had been sentenced to penal servitude for their part in the rising, Thomas Ashe, principal of Corduff NS, and a member of the Dublin Central Association of the INTO, and Finian Lynch, of St Michan’s BNS. Ashe, who had led a battalion of Volunteers in North County Dublin, had led what was probably the most militarily successful sortie of Easter Week, while Lynch had been based around North King Street. Teachers who had been interned but since released (about ten men) ‘and in respect of whom report had been received from Dublin Castle’ would be allowed to resume and the managers of the remaining teachers who were arrested and had not yet been released were told they could not resume teaching without the Commissioners’ sanction. Those teachers who had not been interned but who were reported to be members of the Volunteers were to be told to resign all connection with the organisation. In all, six teachers, four as well as Ashe and Lynch, had their recognition withdrawn. Of these four, one, Michael Thornton (Mícheál Ó Droighnáin), appealed the decision, initially with the support of his local INTO branch, and much later the CEC, and was eventually reinstated as principal of Furbough National School in 1920. In addition to keeping an eye on the teachers, the Board also reviewed the books being used in schools, in particular the history books, and withdrew a couple of Irish history readers which could possibly be deemed problematic. Finally, they sanctioned the distribution of a pamphlet written by May C. Starkie, the wife of WJM Starkie, the Resident Commissioner of Education, entitled ‘What is patriotism: the teaching of patriotism’, described by the Bishop of Limerick as a recruiting manifesto from ‘an educational Mrs Proudie’.

Apart from the early response by George Ramsay to Mahaffy’s accusations and the piece in the Times Education Supplement, the INTO, as a whole had nothing to say on the matter of 1916. This might well have been expected. The Rules of National Schools, under which teachers were employed, placed them, individually and collectively, outside the bounds of political life. They were ordered ‘to avoid fairs markets and meetings – but above all, political meetings of every kind; [and] to abstain from controversy…’ while an additional rule reiterated that ‘the attendance of teachers at public meetings or meetings held for political purposes, or their taking part in elections except by voting, [was] incompatible with the performance of their duties and a violation of rule which will render them liable to withdrawal of salary.’ National teachers had long resented the curbs on their civic lives and had been campaigning for ‘full civil rights’ for several years, with the Board of National Education opposing any loosening of the rule. But while the INTO was prohibited from comment on politics by the Commissioners, it was, perhaps more pertinently, prohibited from so doing by its own rules. Established in 1868 as an organisation representing all the national school teachers of Ireland regardless of religion, the second rule of the organisation was designed to ensure the unity of national teachers was not threatened by sectionalism, declaring that ‘no political or sectarian topics shall be introduced at meetings of the National Teachers’ Association, and any Association which permits the discussion of sectarian or political topics shall be obliged to sever its connection with the general organisation.’ There had been periodic tensions over questions of politics and religion (the two were almost inevitably intertwined), and on one occasion, a failure to drink a loyal toast to the Lord Lieutenant at the Congress of 1883 ultimately led to a short-lived breakaway Northern Teachers Union which returned to the fold in 1889, to relief all round. Ten years later, a ginger group was established calling itself the Protestant National Teachers Union (PNTU), its purpose to represent teachers working in schools under protestant management within the INTO, their primary purpose to secure for protestant teachers similar rights of tenure that had been conceded to Catholic teachers during the 1890s. Notably, though, the PNTU existed so that they would not be taken for granted, with one reason for joining the IPNTU being ‘because if at any future time the INTO should adopt any principles or methods repugnant to Protestant sentiment, we would have in union an organisation to fall back upon, and could, without disadvantage, sever our connection. Further, the knowledge that we could do so might be the most powerful preventative against the adoption of wrong lines by the INTO.’

The INTO may not have adopted any ‘wrong lines’ over the rising having adopted no line at all, but a deep difference of opinion soon became apparent nonetheless when the IPNTU met for its annual conference in Belfast on 24 June. Presided over by George Ramsay who was president of the IPNTU as well as the INTO, delegates unanimously adopted a motion which declared their ‘whole-hearted and unaltered loyalty and devotion to our King and Empire, and our indignant condemnation of a section of our countrymen in trying to raise a rebellion in Ireland at the dictation of, and with the assistance of Germany,’while more practically the PNTU established a subcommittee ‘to watch protestant teachers’ interests in the so-called Irish question’. It’s worth bearing in mind that only days after that conference, the big push began at the Somme on 1 July and by 2 July the death toll among the officers and men among the 36th Ulster Division was some 5,500, a factor which would only reinforce the antipathy towards the rebels from the (largely Ulster based) protestant INTO members. The Belfast branch of the INTO also ‘[disclaimed] all sympathy with disloyalty to the Crown’ but it was unusual in this. For the most part, comment from local associations, where there was any, was more inclined to condemn Mahaffy’s statement as libellous and grossly insulting but also to vehemently oppose any effort to introduce pledges of loyalty for teachers.

In the end, the Commissioners having declared Mahaffy’s accusations to be hollow as early as July, there was little further action taken at a general level. As such, the 1916 Rising had no real immediate impact on the professional lives of teachers or their organisation and the INTO did not involve itself but the transformation of the political context over the next two years, in part as a result of the Rising (but also due to the on-going war in Europe) challenged the commitment among INTO members to eschew politics in order to preserve teacher unity. Ostensibly, the INTO remained detached from politics most obviously on the occasion when Thomas Ashe died from force feeding while on hunger strike in September 1917. This was a landmark event in the country at the time, with his funeral described as ‘even more impressive than the funeral of Parnell,’ the School Weekly published only a small headshot in its ‘Mainly Personal’ section, noting only that he had ‘died under such tragic circumstances,’ and was ‘sincerely mourned by all who knew him’.The following month saw the IPNTU pass a motion which ‘[deprecated] the actions of the Central Committee of the INTO in passing a resolution of sympathy with political offenders’ (presumably Ashe), a motion which, significantly, did not appear in the published minutes of the CEC around that time. The change in the political context after 1916 inevitably impacted on the organisation and when, in September 1917, a majority voted that the INTO should affiliate to the Irish Trade Union Congress and Labour Party, a body regarded by this time as separatist socialist organisation, the die was cast while the INTO’s subsequent participation in the ITUCLP led anti-conscription campaign in 1918, was the last straw making it ‘impossible for many northern teachers to remain a constituent part of the INTO’, and leading to the formation of the Ulster Teachers Union (UTU) in 1919, the first group to secede from the INTO which never rejoined. After partition, the INTO continued to represent teachers in schools under Catholic management in Northern Ireland as well as a significant section of Protestant teachers in county schools who remained with the organisation. It was the INTO’s affiliation with the ‘Bolshevik’ Congress and Labour Party that hastened the departure of some of its more conservative Protestant members but while the 1916 Rising may not in itself have caused the partition of the INTO, but it was, arguably a catalyst nonetheless.